SAN FRANCISCO, Jan. 28 — A year ago Jacqui Rogers, a retiree in southern Oregon who dabbles in vintage costume jewelry, went on eBay and bought 10 butterfly brooches made by Weiss, a well-known maker of high-quality costume jewelry in the 1950's and 1960's.

At first, Ms. Rogers thought she had snagged a great deal. But when the jewelry arrived from a seller in Rhode Island, her well-trained eye told her that all of the pieces were knockoffs.

Even though Ms. Rogers received a refund after she confronted the seller, eBay refused to remove hundreds of listings for identical "Weiss" pieces. It said it had no responsibility for the fakes because it was nothing more than a marketplace that links buyers and sellers.

That very stance — the heart of eBay's business model — is now being challenged by eBay users like Ms. Rogers who notify other unsuspecting buyers of fakes on the site. And it is being tested by a jewelry seller with far greater resources than Ms. Rogers:

Tiffany & Company, which has sued eBay for facilitating the trade of counterfeit Tiffany items on the site.

If Tiffany wins its case, not only would other lawsuits follow, but eBay's very business model would be threatened because it would be nearly impossible for the company to police a site that now has 180 million members and 60 million items for sale at any one time.

Of course, fakes are sold everywhere, but the anonymity and reach of the Internet makes it perfect for selling knockoffs. And eBay, the biggest online marketplace, is the center of a new universe of counterfeit with virtually no policing.

EBay, based in San Jose, Calif., argues that it has no obligation to investigate counterfeiting claims unless the complaint comes from a "rights owner," a party holding a trademark or copyright. A mere buyer who believes an item is a fake has almost no recourse.

"We never take possession of the goods sold through eBay, and we don't have any expertise," said Hani Durzy, an eBay spokesman. "We're not clothing experts. We're not car experts, and we're not jewelry experts. We're experts at building a marketplace and bringing buyers and sellers together."

Company officials say they do everything they can to stop fraud. The company says only a minute share of the items being sold at any given time — 6,000 or so — are fraudulent. But that estimate reflects only cases that are determined by eBay to be confirmed cases of fraud, like when an item is never delivered.

Experienced eBay users say that the fraud goes well beyond eBay's official numbers, and that counterfeiters easily pass off fakes in hundreds of categories.

"EBay makes a lot of money from a lot of small unhappy transactions," said Ina Steiner, the editor and publisher of

AuctionBytes.com, an online newsletter. "If you've lost a few thousand dollars, you might go the extra mile to recover it. But if you've lost $50 or $20 you may never be able to prove your case, and in the meantime eBay has gotten the listing fee and the closing fee on that transaction."

The Tiffany lawsuit, in addition to accusing eBay of facilitating counterfeiting, also contends that it "charges hundreds of thousands of dollars in fees" for counterfeit sales.

In 2004, Tiffany secretly purchased about 200 items from eBay in its investigation of how the company was dealing with the thousands of pieces of counterfeit Tiffany jewelry. The jeweler found that three out of four pieces were fakes.

The case will go to trial by the end of this year, said James B. Swire, an attorney with Arnold & Porter, a law firm representing Tiffany. The legal question — whether eBay is a facilitator of fraud — is a critical issue that could affect not only eBay's future but Internet commerce generally, said Thomas Hemnes, a lawyer in Boston who specializes in intellectual property.

"If eBay lost, or even if they settled and word got out that they settled, it would mean they would have to begin policing things sold over eBay, which would directly affect their business model," Mr. Hemnes said. "The cost implied is tremendous."

But eBay members like Ms. Rogers have little desire to wait for court decisions; they say that the uncontrolled flood of fakes is driving down the value of the authentic goods.

For the past few months, Ms. Rogers and three women she met on eBay who are also costume jewelry buffs have banded together to track the swindlers they say are operating in their jewelry sector. "People have faith that eBay will take care of them, but it doesn't," Ms. Rogers said. "EBay has done nothing."

Carrie Pollack, who sells jewelry from her home in Sudbury, Mass., and is part of Ms. Rogers's group, said an authentic Weiss brooch of good quality could command $150. But she said the profusion of counterfeits had confused the market and diluted the value of such a pin to as little as $30.

"It's a situation that's facing all of us in the jewelry world, and I suspect other decorative arts as well," said Joyce Jonas, an antique jewelry specialist in New York. "It's totally out of control."

Over the past few months Ms. Rogers and her team have reported to eBay more than a thousand jewelry listings they believe to be fakes; only a few listings have been removed.

The women say that by watching the listings they have uncovered a ring of a half-dozen or so counterfeiters, most of them living in Rhode Island within a few miles of one other. They say the sellers supply one another with fake jewelry, conceal the fact that they are buying from one another to boost their seller status, and regularly dole out positive feedback to each other to fool potential buyers.

Ms. Pollack was unaware of the abundance of counterfeit pieces on eBay when she paid $360 for what she thought were genuine pieces of Weiss jewelry. She demanded a refund from the seller, who refused.

Ms. Pollack said it wasn't until she filed a formal complaint with PayPal, eBay's online payment system, that the seller offered to refund her money. Since then, she has sent eBay officials a raft of evidence pointing out the presence of the counterfeits, including an independent appraisal from Gary L. Smith, a gemologist in Montoursville, Pa., who declared the five brooches Ms. Pollack sent him to be unmistakable fakes.

This reporter, too, sent a butterfly brooch with "Weiss" stamped on the back, purchased for $12.99 recently from one of the alleged counterfeiters, to Mr. Smith. He determined that there was nothing vintage about it — certainly not the very new glue used to hold in the glass stones. (In a subsequent phone conversation, the seller, Garnet Justice, who lives in Leesburg, Ind., said she had "no idea" whether the pin was authentic, and offered a full refund.)

Antoinette Matlins, another gemologist, also purchased five vintage pieces from the sellers tracked by Ms. Rogers's group to determine their authenticity. She found them to be cheap knockoffs worth less than 10 percent of their sale prices.

But she was not surprised. Whether online or off, she said, "fraud is rampant in any venue where you are looking for a steal."

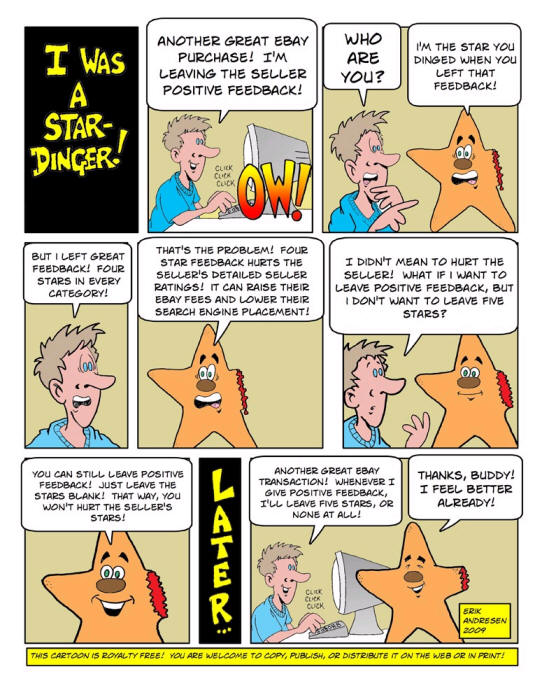

EBay's feedback system that allows buyers to post negative reviews of bad sellers is supposed to protect customers like Ms. Pollack. Yet all of the alleged counterfeiters had consistently positive ratings.

Ms. Steiner of AuctionBytes.com said this situation was not uncommon. Buyers and sellers are often reluctant to leave bad reviews, lest their own reputations suffer.

EBay does not allow members to contact other potential buyers to warn them of possible fraud. Otherwise, said Mr. Durzy, it would be too easy for someone to try to ruin the reputation of a legitimate rival.

Ms. Rogers said she had no qualms about breaking the rules by contacting buyers about fakes she spots. In November, she even put up a listing that advertised a fake Christmas tree brooch from Eisenberg Ice, a vintage costume jewelry maker, just to make people aware of the fraud.

"The reason I am doing this is because eBay won't," the listing read. "Let's stop this madness — these fakes are pushing down the price of authentic jewelry."

"The frustrating part is that eBay just stands back and lets these people make thousands and thousands of dollars" while taking a fee for each transaction, Ms. Rogers said. (The company's profits rose 36 percent in the last quarter from the year before, to $279.2 million.)

After the spectacular case in 2000 when a fake Richard Diebenkorn painting was nearly sold for $135,000 on eBay, the company put in place a handful of safeguards, like the PayPal buyer protection plan, an improved system for spotting eBay policy violations, and improved detection of fraud in general. But when it comes to counterfeit goods, the problem has gotten worse.

Artwork is particularly vulnerable to counterfeiting. "The majority of things that appear on eBay are fakes," said Joel Garzoli, an art gallery owner in San Rafael, Calif.

Mr. Durzy argued that "if we began to automatically pull listings for things reported to us as fake, we could be pulling listings that are legitimate." He added that the company had to rely on trademark owners to "tell us something is counterfeit." Yet trademark owners like Tiffany say they have gotten no relief.

Ms. Rogers and her team say their efforts may be working. The number of bids on the fake vintage jewelry pieces has dropped sharply since they went into action, they say. Nonetheless, the seller who sold Ms. Pollack the knockoff is still in business and recently put up for sale a "beautiful Weiss brooch with lots of sparkle and shine." Starting bid: $9.99.